Fumi Imamura’s floral works

Fumi Imamura in her studio in Aichi, Japan. Photography by Norihito Hiraide

Interview with Japanese artist Fumi Imamura opens a series of conversations with artists participating in ‘New Nature’ exhibition at PATERSON ZEVI gallery London, curated by Julia Tarasyuk and organized with IKEBANA projects.

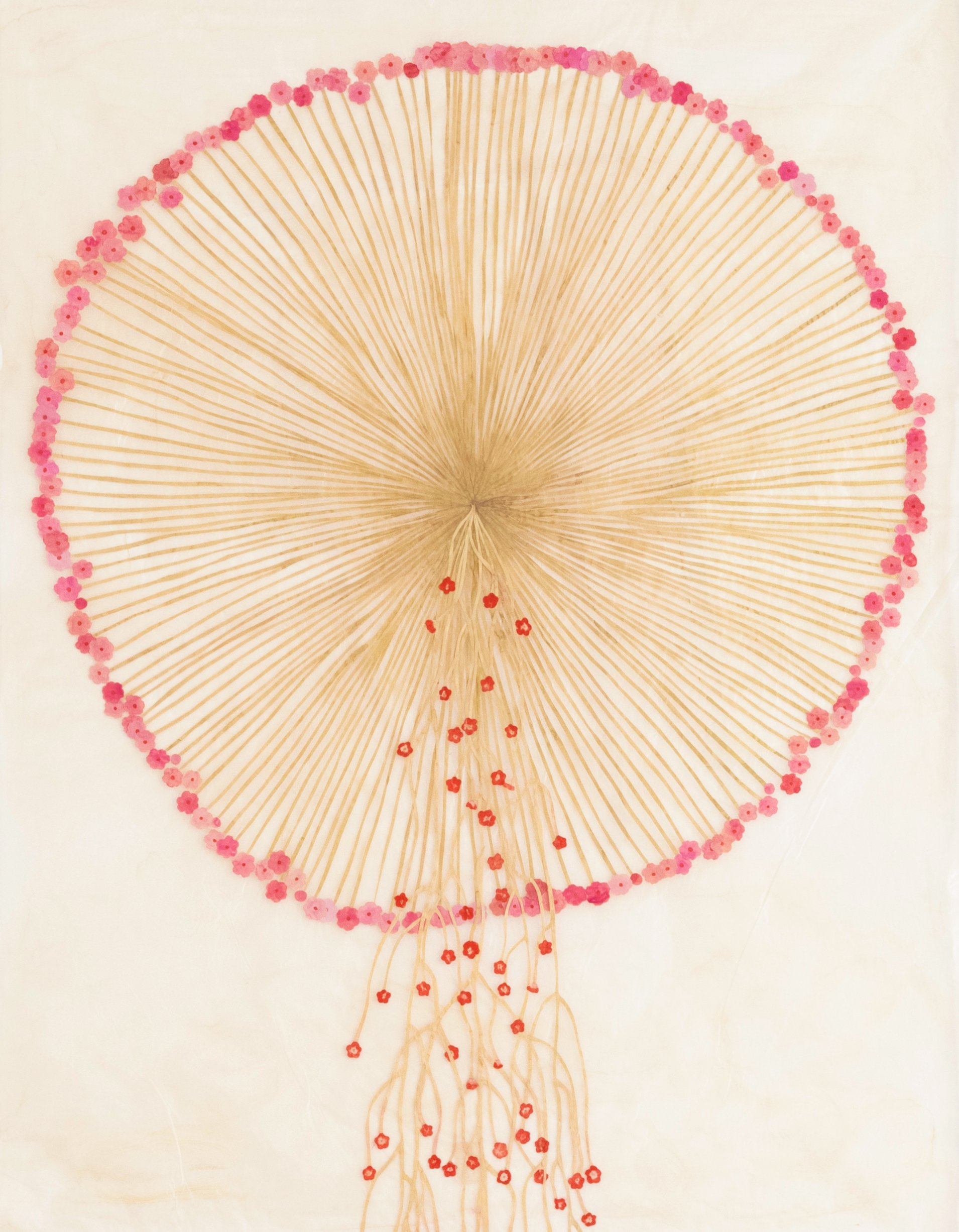

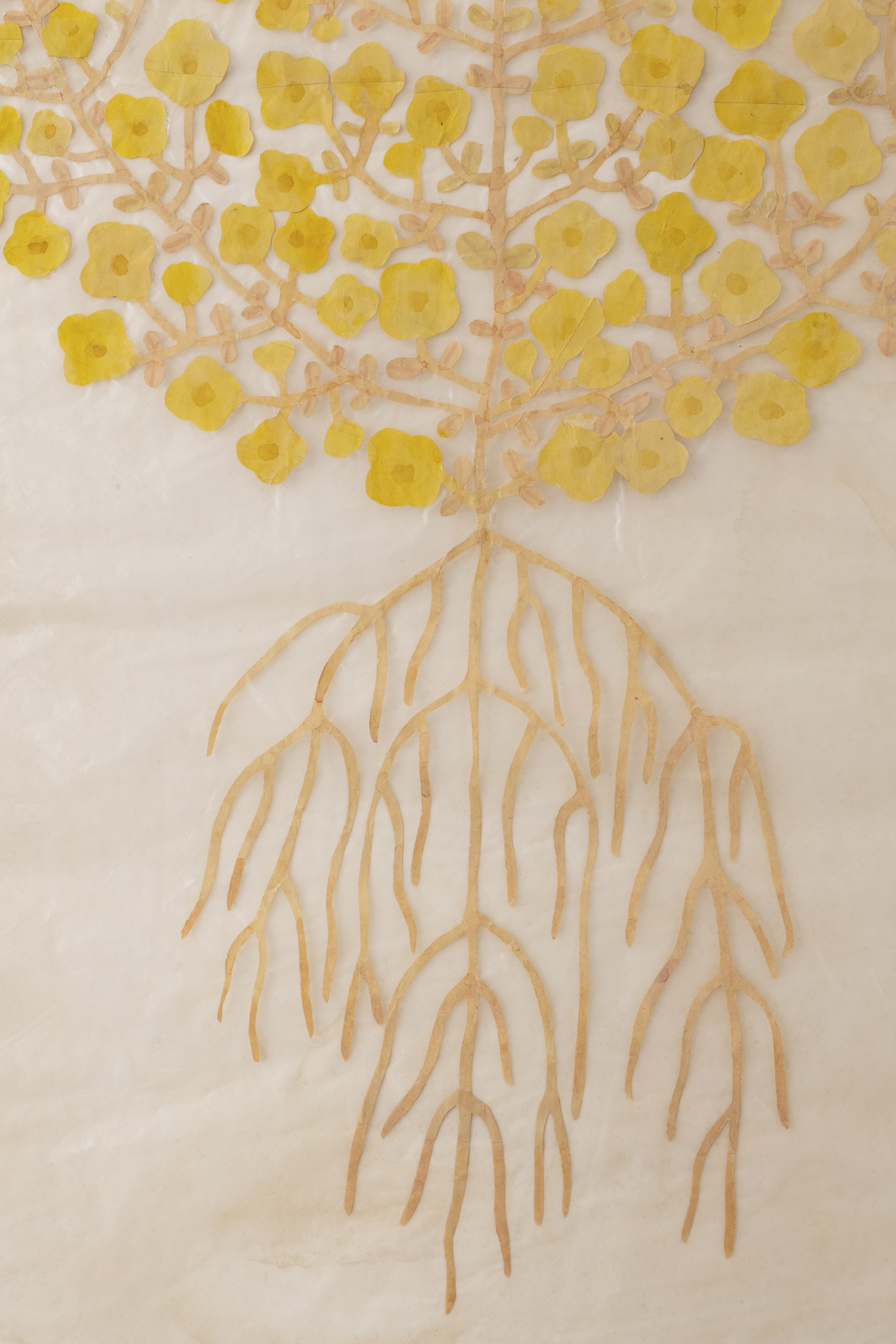

Fumi Imamura 今村文 (b. 1982, Aichi Prefecture, Japan) is a contemporary artist who uses encaustic wax painting, an ancient technique once applied to the coffins of mummies, to create glossy, crinkly floral works on paper. Her delicate creations resemble dried flowers pressed into the pages of a book, but on a wall-sized scale. These plants derive their charm not only from their branching, budding, insect-nibbled blossoms and leaves, but also from their poignantly rendered roots. Imamura’s works speak to the beauty of the cracked, the faded, and the lovingly preserved.

Her collages on semi-transparent wax paper feature delicate botanical motifs inspired by the landscape of her native Aichi prefecture in central Japan. Meticulously crafted tiny floral elements are arranged in surreal shapes that the artist borrows from nature to express her own body and mind and imagine a world with an organic sense of freedom.

‘New Nature’, PATERSON ZEVI, London, on view until 15 July 2022. To book an appointment or for further information, please email info@patersonzevi.com

How did the floral subject appear in your work? What interests you the most in the botanical world?

When I was a student, I decided that I would draw exclusively flowers. This is because I have loved plants since I was a child and found painting flowers to be the most enjoyable thing to do. Human beings don’t have the ability to change their body whereas plants can grow branches and spread their leaves.

When I try to express my own body and mind, I feel that I can be much freer to express myself by borrowing the form of a plant than the form of a human being.

What interests me about the plant world is that plants have no cranial nerves and relate to the world as open internal organs. I came to know this as the idea of the anatomist Shigeo Miki. The novelist Kyusaku Yumeno said that 'the brain is not a place to think', while Shigeo Miki said that 'the brain is merely a mirror reflecting the internal organs'. We tend to think that the brain is the essence of a person, but rather the brain is an accessory organ. A plant that lives only with its visceral organs is very simply connected to the world and does not question it. I sometimes think that this is a happiness that people have forgotten.

Fumi Imamura, Circle and Root, 2022. Installation view, PATERSON ZEVI gallery, London. Photography by Will Amlot

Your shapes and forms inspired by nature have a mystical air about them. Do you see them as continuation of nature or something separate?

I don't try to recreate actual plants, but I am always inspired by their presence, shapes and colours. Plants as decoration are also an important element for me. I like flowers in my daily life, for example in embroidery and floral patchwork. When I look at worn-out floral patterns, I feel gentle. There is a human presence and emotion through the flowers. There is no linguistic meaning in the way the decorative plants stretch their branches and sway their heavy flowers, but I feel a wordless poetry in them. Along with the independent theme of 'plants', I am interested in the idea of 'people painting plants'.

Fumi Imamura cutting paper. Photography by Norihito Hiraide

Tell us a little bit more about your unique technique.

I make my work by cutting out drawings on paper and pasting them back onto the paper. I also overlap and change the shape when pasting them together. It's hard to tell from the image, but the actual piece isn’t flat. I think it's interesting how something that was flat becomes three-dimensional by cutting it out, and then back to flat again. The paper is also made from plants, so the flower motifs become very realistic.

We have been lucky to attend your incredible exhibition at the historic Shiseido gallery in Tokyo a couple of years ago where you transformed the space in large scale installations of domestic environments covered with overgrown vegetation. What was the story behind it?

The exhibition at the Shiseido Gallery was a rare opportunity that I got through an open call. Under the title Invisible Garden, I recreated my own bedroom in the gallery and created a world in which flowers and insects infested it. The novel Dogura magura by Kyusaku Yumeno was the inspiration for this work, which addressed the absence while sleeping.

I created this work based on my fantasy that I do not exist while I am asleep, and that going to sleep and waking up means that I die once and am reborn every day. I exhibited flowers and insects as if I were dying and decomposing. This exhibition has become an important thing for me.

Invisible Garden, Shiseido Gallery, Tokyo (2019). Photography by Ken Kato

Japanese culture has a very special relationship with nature, flowers and plants. Does it find reflection in your work?

I have never made my work with Japanese culture in mind, but I believe that as long as I live in the Japanese climate, I am influenced by it. In Japan, there is a belief that everything has a god, and I believe the same.

Have you encountered Ikebana before? What do you think of this ancient practice and the way it becomes a modern art form today?

Ikebana was one of the most common things that many people learnt in my grandmother's generation, along with tea and cooking, as part of the training for brides. I never learnt it, but my grandmother always had flowers in her tokonoma and at the entrance.

It's a strange thing, flowers look so much tighter in style when they are arranged in this way. I also thought Kuniko Donen's ikebana work, which I met in Kanazawa, was wonderful. Like my own work, I am attracted to things that are an extension of my daily life, rather than being there as art.

Details of Fumi Imamura’s works currently on view at PATERSON ZEVI gallery in London. Photography by Will Amlot